Douglas Coupland was my favourite author around the turn of the century – from when I randomly stumbled upon Microserfs in the library twenty years ago when I was 17 … to I don’t know, 2002-ish? when I started a new phase of my life.

These four were by far my favourite books of his and I re-read them regularly until about ten years ago – this is my first read-through since then. I’m reviewing them in chronological order, because it makes sense to plot Coupland’s (and my own) trajectory etc, but I read them in the order in the title (not that it really matters – or maybe it does).

Jump down to:

Generation X

Lacking a strong driving story arc or indepth character analysis, it’s hard to review this book in a conventional way. It’s part parable-stuffed framed narrative, part hipster-code-word dictionary. Even the sections of traditional narrative – when Andy goes home to visit his family or his drive to Mexico – are so beautifully poetically indulgent and dreamlike that they feel allegorical: the incidents are not as extreme as those that happen in later Coupland novels but they’re not realistic either. It’s a postmodern art piece more than a novel really – and like nearly all art, it does not exist within its own vacuum but it is shaped by its relationship with the viewer.

All of these books are in that special category for me – of media I first encountered when I was years, a decade or more even, younger than the characters but now I’m the same age or older than them. Generation X is interesting to me though because from the age of 17 until now, the age of 37, I feel like I’ve constantly identified with the characters as peers – not on the surface (born in the very last cohort of GenX, I had missed many of the cultural touchstones they reference or experience, like Vietnam or the overriding threat of nuclear war) but on an emotional level. (I believe) Coupland wrote the book to be about a group of people at a specific age (that Generation X) in a specific time (the end of history) but a lot of the characters’ experiences have persisted since then. Because of that and a few dated references aside, there is a new timelessness to the book: the ‘poverty jet set’, the people shut out/afraid of homeownership, those having a ‘mid-20s crisis’, the McJobs, and people feeling that they are living in a period where (almost simultaneously) too much and too little is happening — all of those things have been taken up and turned into a million Buzzfeed articles for Millenials to devour. (I also think Dag’s “cuddly nuclear bombs” theory has come true but it’s too long to go into here.)

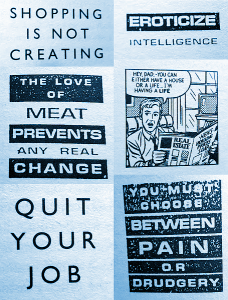

Though it is a slight book, I think ‘Generation X’ has benefited from re-reads over the years. Each time I come back to it, I bring something new to it – where I am in life, how I feel, what I’ve discovered about myself and others – and I get something new out the stories that the characters share or find a fresh resonance in the little out-of-context text blocks scattered throughout.

Though it is a slight book, I think ‘Generation X’ has benefited from re-reads over the years. Each time I come back to it, I bring something new to it – where I am in life, how I feel, what I’ve discovered about myself and others – and I get something new out the stories that the characters share or find a fresh resonance in the little out-of-context text blocks scattered throughout.

I can also point to different parts and remember how I felt when different points of it leapt out at me – re-reading it is like re-experiencing my life. I also note with a nod that early reads planted seeds within me which I later ran with, most notably the proto-‘beautiful thing‘ memory recounting episode:

“After you’re dead and buried and floating around whatever place we go to, what’s going to be your best memory of earth? What one moment for you defines what it’s like to be alive on this planet. What’s your takeaway? Fake yuppie experiences that you had to spend money on, like white water rafting or elephant rides in Thailand don’t count. I want to hear some small moment from your life that proves you’re really alive.”

It is an essential book in my collection but I don’t think I can recommend the book to others any more. I’ve tried a few times and it’s not been very warmly received – probably because it’s a bit odd. I’m glad I found it when I did, and I look forward to it ageing and evolving with me.

Choice quotes:

“I broke out into a sweat and the words of Rilke, the poet, entered my brain — his notion that we are all of us born with a letter inside us, and that only if we are true to ourselves, may we be allowed to read it before we die.”

“There. I always wanted to do that.”

“Oh Andy … do you know what this is like? It’s like the dream everyone gets sometimes – the one where you’re in your house and suddenly discover that a new room that you never knew was there. But once you’ve seen the room you say to yourself ‘Oh how obvious – of course that room is there. It always has been.'”

“You give me and my friends a bum rap but I’d give all of this up in a flash if someone had a remotely plausible alternative. … I just get so sick of being jealous of everything … And it scares me that I don’t see a future. And I don’t understand this reflex of mine to be a smartass about everything. It really scares me. I may not look like I’m paying attention to anything, Andy, but I am. But I can’t allow myself to show it. And I don’t know why.”