Douglas Coupland was my favourite author around the turn of the century – from when I randomly stumbled upon Microserfs in the library twenty years ago when I was 17 … to I don’t know, 2002-ish? when I started a new phase of my life.

These four were by far my favourite books of his and I re-read them regularly until about ten years ago – this is my first read-through since then. I’m reviewing them in chronological order, because it makes sense to plot Coupland’s (and my own) trajectory etc, but I read them in the order in the title (not that it really matters – or maybe it does).

Jump down to:

Generation X

Lacking a strong driving story arc or indepth character analysis, it’s hard to review this book in a conventional way. It’s part parable-stuffed framed narrative, part hipster-code-word dictionary. Even the sections of traditional narrative – when Andy goes home to visit his family or his drive to Mexico – are so beautifully poetically indulgent and dreamlike that they feel allegorical: the incidents are not as extreme as those that happen in later Coupland novels but they’re not realistic either. It’s a postmodern art piece more than a novel really – and like nearly all art, it does not exist within its own vacuum but it is shaped by its relationship with the viewer.

All of these books are in that special category for me – of media I first encountered when I was years, a decade or more even, younger than the characters but now I’m the same age or older than them. Generation X is interesting to me though because from the age of 17 until now, the age of 37, I feel like I’ve constantly identified with the characters as peers – not on the surface (born in the very last cohort of GenX, I had missed many of the cultural touchstones they reference or experience, like Vietnam or the overriding threat of nuclear war) but on an emotional level. (I believe) Coupland wrote the book to be about a group of people at a specific age (that Generation X) in a specific time (the end of history) but a lot of the characters’ experiences have persisted since then. Because of that and a few dated references aside, there is a new timelessness to the book: the ‘poverty jet set’, the people shut out/afraid of homeownership, those having a ‘mid-20s crisis’, the McJobs, and people feeling that they are living in a period where (almost simultaneously) too much and too little is happening — all of those things have been taken up and turned into a million Buzzfeed articles for Millenials to devour. (I also think Dag’s “cuddly nuclear bombs” theory has come true but it’s too long to go into here.)

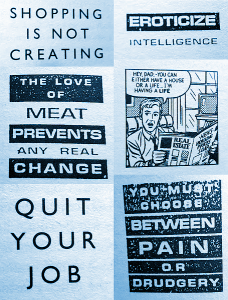

Though it is a slight book, I think ‘Generation X’ has benefited from re-reads over the years. Each time I come back to it, I bring something new to it – where I am in life, how I feel, what I’ve discovered about myself and others – and I get something new out the stories that the characters share or find a fresh resonance in the little out-of-context text blocks scattered throughout.

Though it is a slight book, I think ‘Generation X’ has benefited from re-reads over the years. Each time I come back to it, I bring something new to it – where I am in life, how I feel, what I’ve discovered about myself and others – and I get something new out the stories that the characters share or find a fresh resonance in the little out-of-context text blocks scattered throughout.

I can also point to different parts and remember how I felt when different points of it leapt out at me – re-reading it is like re-experiencing my life. I also note with a nod that early reads planted seeds within me which I later ran with, most notably the proto-‘beautiful thing‘ memory recounting episode:

“After you’re dead and buried and floating around whatever place we go to, what’s going to be your best memory of earth? What one moment for you defines what it’s like to be alive on this planet. What’s your takeaway? Fake yuppie experiences that you had to spend money on, like white water rafting or elephant rides in Thailand don’t count. I want to hear some small moment from your life that proves you’re really alive.”

It is an essential book in my collection but I don’t think I can recommend the book to others any more. I’ve tried a few times and it’s not been very warmly received – probably because it’s a bit odd. I’m glad I found it when I did, and I look forward to it ageing and evolving with me.

Choice quotes:

“I broke out into a sweat and the words of Rilke, the poet, entered my brain — his notion that we are all of us born with a letter inside us, and that only if we are true to ourselves, may we be allowed to read it before we die.”

“There. I always wanted to do that.”

“Oh Andy … do you know what this is like? It’s like the dream everyone gets sometimes – the one where you’re in your house and suddenly discover that a new room that you never knew was there. But once you’ve seen the room you say to yourself ‘Oh how obvious – of course that room is there. It always has been.'”

“You give me and my friends a bum rap but I’d give all of this up in a flash if someone had a remotely plausible alternative. … I just get so sick of being jealous of everything … And it scares me that I don’t see a future. And I don’t understand this reflex of mine to be a smartass about everything. It really scares me. I may not look like I’m paying attention to anything, Andy, but I am. But I can’t allow myself to show it. And I don’t know why.”

Microserfs

‘Microserfs’ has a lot in common with ‘Generation X’ both thematically and tonally.

‘Generation X’ – a book about people adrift in life, coming through breakdowns and working McJobs – is surprisingly optimistic. The three main characters have all crashed in one way or another and are lost – but by coming together, they become found again. (I’m not going so far to say they ‘find themselves’, whatever that means, but in finding each other, they stop being lost – if you know what I mean.) ‘Microserfs’ is very much about this too – to stretch an analogy the characters would understand, these individual processes crash alone but come together to form a working program. Coupland has swapped palm trees for cedars but the characters, all from “zero kidney” families and with “stalwart, sensible, unhuggable names”, could very easily be friends in the same story.

Similarly, like with ‘Generation X’, my experience of ‘Microserfs’ is continually wrapped up with the progress of my life: my copies are filled with mementos tracking the passage of time – bus ticket bookmarks, pressed flowers and even the receipt from the Coupland book signing I attended in 2003. (It’s the case with the latter two books too; less so with them, but you’ll see I still have to explain my situation as much as the books.)

I first read Microserfs in early 1997. I saw it in the town library – the yellow, Lego-like cover leapt out at me from amongst the Barbara Taylor Bradford/Danielle Steele hardbacks lining the shelves. I was so hungry for escapism then – and so limited by the selection in a small elderly town – that I picked it up without knowing anything about it. Is it too grand to say that blind selection changed my life? If so, it’s only a small exaggeration. It’s easy to point at its most direct influences (for example, it interested me in Bill Gates & Microsoft, so when we had to pick a presentation topic in the first term of university, I joined the group that were covering the impact of Microsoft; my group mates would become my best friends throughout university and would, explicitly, lead me to where I am today) but that’s less interesting than the stuff that’s harder to pinpoint. It got me asking dozens of questions I hadn’t considered before and who knows how they changed me along the way. I don’t think it’s a just coincidence that my favourite people nowadays tend to be thoughtful computer programmers, who would all get as excited by the Handbook of Highway Engineering as the characters in the book.

Despite the title, the group of characters don’t actually spend that much of the book working for ‘Microsoft’: the majority of the time they’re working at their own start-up, in recovery from the years they spent as cogs in the megacorp, blossoming into real people again after years of being interchangable people-units with “no life”. Passing references to salaries, 14.4 modems or Apple’s shaky financial status aside, it remains even more surprisingly timeless than ‘Generation X’: though we’re not in Silicon Valley (or even Silicon Roundabout), we’ve been close enough to start-up culture to know that many of the issues (funding crises, marketing bullshit and constant hype about everything) still apply – and of course, the megacorps still lure in young programmers with free snacks then wring them dry. I know dozens of people – myself included to some extent – that made the same leap away from corporations or other big organisations in their mid-to-late 20s – all of us chasing some sense of One-Point-Oh or actually making a difference in the world beyond than “a computer on every desk and in every home”. Similarly, Susan’s Chyx crusades seem as relevant now as then and what is Minecraft if not Oop brought to life?

It’s quite a heightened book – the elevated nature of the conversations lampshaded early on when Dan says Karla speaks like she’s a “Star Trek episode made flesh” – and as a faux-journal, it is understandably a somewhat disjointed stream of consciousness. But at the same time, it is perhaps the most satisfying of Coupland’s early works in terms of story-telling: the strands of philosophy, theory and text manipulation (pages of binary; repeats of pages but with either the consonants or vowels removed; random word dumps) that are explored in the book all come together neatly in the end. The novel isn’t flawless by any means – some of the characterisation is rather flat and I think a longer time span would have helped the flow of most of the story arcs – but the conclusion ultimately gives everything that has come before it a purpose.

Out of all the Coupland books I adored way back when, ‘Microserfs’ was by far my favourite at the time and I collected multiple copies of it so that I could lend them out with free abandon. I currently own a ridiculous six copies of it: three generic paperbacks, a first edition US print, a first edition UK print and an uncorrected proof. I have read them all countless times and I have to admit that this re-read was possibly the least illuminating in terms of revelations from the text – but I still enjoyed it. After so much repetition of them over the years, there is a certain rhythm to the words that makes it as comforting to me as an old favourite song – I read it with the same blissed out “I’m home!” expression that I use when watching ‘Wayne’s World’. I don’t imagine I’ll read it again for, perhaps, even another decade but those books, all those books are staying on the shelf.

Choice quotes:

What is human behavior, except trying to prove that we’re not animals?

“Beware of the corporate invasion of private memory.”

“The belief that tomorrow is a different place from today is certainly a unique hallmark of our species.”

We generate stories for you because you don’t save the ones that are yours.

“I’m trying to debug myself.”

“You know how when somebody says, ‘Remember that party at the beach last year?’ and you say ‘Oh God, was that last year? It feels like last month’? If I’m going to live a year, I want my whole year’s worth of a year. I don’t want it feeling like only one month.”

“We look at a flock of birds and we think one bird is the same as any other bird – a bird unit. But a bird looks at thousands of people at a Giants game up at Candlestick Park, say, and all they see is ‘people units’. We’re all as identical to them as they are to us. So what makes you different from me? Him from you? Them from her? What makes any one person any different from any other? Where does your individuality end and your species-hood begin? As always, it’s a big question on my mind.”

“I used to care about how other people thought I led my life. But lately I’ve realised that most people are too preoccupied with their own lives to give anyone even the scantiest of thoughts.”

“There’s one thing that computing teaches you, and that’s that there is no point to remembering everything. Being able to find things is what’s important.”

Girlfriend in a Coma

In ‘Generation X’, when Andy first meets Claire, her extended family have fled to Palm Springs in the desert, to escape what they think will be an apocalyptic-level earthquake in Los Angeles. Andy muses that when people start wistfully talking about the approaching ‘End Days’, it’s a sign that something else is going badly wrong in their lives and, essentially, the complete destruction as life as we know it is the only way they can picture the future. ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ is worked example of that: Coupland admits that ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ wasn’t consciously planned but more of “an eruption” during “one of the darkest periods of [his] life”.

Out of these four books, my experience of this is less tied to my life at the time – though I can tell you with certainty that I got my copy of it from the Oxfam bookshop that used to be in Cambridge Arcade in Southport — the week it was published, in perfect hardback. And unlike collect-em-all approach with ‘Microserfs’, that remained my only copy until last month, when I bought a cheap used paperback for this re-readathon. I’m not a fan of form factor of hardback books – even neat, not-oversized ones like ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ – so I haven’t re-read it as much as the others but whenever I do read it, it stays with me for sometime – a tingling sensation of what-if.

The girlfriend of ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ is Karen, who falls unconscious at the age of 17 and remains in stasis as those around her grow up and into middle age. When she finally wakes up after nearly 18 years, she is able to cast a fresh eye on the modern world, the lives that her friends are obliviously leading now and how different they are from what they’d hoped for. There’s an apocalypse in which everyone else in the world dies but that’s really just a trifling plot point – the book is really about this group of characters being forced to reassess the world and their place in it.

“Would you have believed in the emptiness of the world if you’d eased into the world slowly, buying its principles one crumb at a time the way your friends did?”

I love the journey of ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ but have never been happy with its conclusion – it took until this re-read for me to identify my main complaint. At the end of the novel, the characters are given a choice – they can either stay in the post-apocalyptic world of decline and hopelessness, or they can go back to the world as it was the day that Karen woke up but from then on, they have to continually, obsessively search for some mystical philosophical truth and urge others to do the same. It’s a fine idea but I find the execution of it, of how far the characters are expected to go, jarringly unrealistic. I understand that the end of the world will have had an impact on them but I don’t believe that the characters – their essences – will be able to change enough to reach that goal. (I think Coupland doubts the possibility of change too: throughout the book, multiple characters repeat how hard it is to change your personality – and Karla in ‘Microserfs’ says something similar as well.) On the surface, the ending feels as optimistic as the two previous books – they get their lives back – but my scepticism has always stopped me enjoying it: I feel almost certain that some of them will fail and will be condemned to the post-apocalyptic hellscape forever. I would have found a gentler version of the same thing more palatable compared to this all or nothing version – I feel like I would have found it more inspirational for my own life because it would be achievable. It’s splitting hairs really but it’s something that’s always niggled me.

The six friends at the centre of ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’ are all different from one another in outlook and attitude, only really united by the coincidence of a shared adolescence and intense experience (Karen’s coma). I often find myself frustrated by such groups in fiction: I know that it allows the author to explore an interesting range of actions and reactions but it also disrupts my immersion, as I get confused why such a disparate group of individuals would actually be friends. Here I think I’m a little more forgiving because it’s not just about being Sporty Spice or Posh Spice for the purpose of a joke but explores the different faces of depression and mental illness: none of the characters are happy or fulfilled, but their unhappiness manifests in different ways, and they use different methods of escapism. So I guess it’s jarring but important. That said, I feel that the story is a little crowded – everyone trying to be a main character rather than supporting artists – and as a result, some of the characters are underdeveloped. This re-read has allowed me to strongly see the threads of these that Coupland picks up again in ‘Miss Wyoming’ – parts of Linus flow into John Johnson, Lois morphs into Marilyn and there are similarities between Pam & Susan too.

Though I have my problems with it, I think it’s easier to recommend this book than either ‘Generation X’ or ‘Microserfs’ – it’s still weird (the third chapter is narrated by a ghost ffs) but has a more conventional structure, and the strange art-y slogans are limited to the chapter headings. It’s about as broadly accessible as Coupland gets in these early books – but that’s not saying that much.

Choice quotes:

“Imagine you’re a forty-year-old, Richard, … and suddenly somebody comes up to you saying, ‘Hi, I’d like you to meet Kevin. Kevin is eighteen and will be making all of your career decisions for you.’ I’d be flipped out. Wouldn’t you? But that’s what life is all about – some eighteen-year-old kid making your big decisions for you that stick for a lifetime.” He shuddered.

“You know, from what I’ve seen, at twenty you know you’re not going to be a rock star. By twenty-five, you know you’re not going to be a dentist or a professional. And by thirty, a darkness starts moving in – you wonder if you’re ever going to be fulfilled, let alone wealthy or successful. By thirty-five, you know, basically, what you’re going to be doing the rest of your life; you become resigned to your fate.”

One of my own stray childhood fears had been to wonder what a whale might feel like had it been born and bred in captivity, then released into the wild – into its ancestral sea – its limited world instantly blowing up when cast into the unknowable depths, seeing strange fish and tasting new waters, not even having a concept of depth, not knowing the language of any whale pods it might meet. It was my fear of a world that would expand suddenly, violently, and without rules or laws: bubbles and seaweed and storms and frightening volumes of dark blue that never end.

What she doesn’t tell Richard though is that in a strange way her old friends aren’t really adults – they look like adults but inside they’re not really. They’re stunted; lacking something. And they all seem to be working too hard. The whole world seems to be working too hard. … People are always showing Karen new electronic doodads. They talk about their machines as though they posses a charmed religious quality – as if these machines are supposed to compensate for their owner’s inner failings. Granted these new things are wonders … but still, big deal.

“I remember when I first woke up how people kept on trying to impress me with how efficient the world had become. What a weird thing to brag about, eh? Efficiency. I mean, what’s the point of being efficient if you’re only leading an efficiently blank life?”

Ask: whatever challenges dead and thoughtless beliefs. Ask: when did we become human beings and stop being whatever it was we were before this? Ask: what was the specific change that made us human? Ask: why do people not particularly care about their ancestors more than three generations back? Ask: why are we unable to think of any real future beyond, say, a hundred years from now? Ask: how can we begin to think of the future as something enormous before us that also includes us? Ask: having become human, what is it that we are now doing or creating that will transform us into whatever it is that we are slated to next become?

Miss Wyoming

Oh poor Miss Wyoming has suffered so! I picked it up – the first of my Coupland re-reads – straight after I had read one of my favourite books – ‘Drop City’ by TC Boyle. The two writing styles could hardly be more different and Coupland’s often sparse, sometimes stilted style came up short compared to Boyle’s dense poetry. But after a few chapters, I settled into the swing of things and I remembered by affection for it.

I remember the first time I read ‘Miss Wyoming’ – it suffered from context then too. I was just finishing up at university and while life was far from rosy (my long term relationship was starting to fall apart and I had the usual what-next anxiety), it felt abundantly full of potential. ‘Miss Wyoming’ is not about life being full of potential – it’s about the flipside of that, when potential has been wrung out of it and you’ve tried to come back, tried to reinvent yourself, not once but twice and it’s failed and failed again, and so how can you possibly move forward now? That first time I read it I can remember thinking the story was a bit ridiculous and I couldn’t identify with the characters, except possibly, just slightly, with Vanessa, who, despite her intellect, has a certain youthful optimism.

Fast forward a couple of years. I was still only 22 but my life’s potential felt like it had leaked out – that long term relationship finally came to an end and I was drifting both personally and professionally, unsure about just about everything. I was reading three or four books a week back then, trying to escape into other worlds, and so it was just a matter of time before I got around to re-reading ‘Miss Wyoming’. When I did, it hit me like a sledgehammer: ‘Miss Wyoming’ is about the painful inevitability of change and loneliness – something that can indelibly stain us, rendering us untouchable but which is almost more taboo than anything else (even now, it feels like it’s easier to talk about depression rather than loneliness). It quickly became one of my favourite books. It doesn’t keep reinventing itself in my eyes like ‘Generation X’ but the core message still resonates with me.

“If he’d learned one thing while he’d been away, it was that loneliness is the most taboo subject in the world. Forget sex or politics or religion. Or even failure. Loneliness is what clears out a room.”

“It hit him that his own form of loneliness was a luxury, one as chosen and as paid for as three weeks in Kenya’s velds or a cherry red Ferrari. Real loneliness wasn’t something an assistant scoped out and got a good price on. Real loneliness was smothering and it stank of hopelessness.”

I still stand by my 20 year old review that the story is a bit ridiculous. Putting the more extravagant parts of ‘Generation X’ aside, there is an grounding realism to Coupland’s early work – the post-college crisis of ‘Shampoo Planet‘ (which I read multiple times but never particularly enjoyed); the largely mundane life of a corporate then start up programmer in ‘Microserfs’; and the beautiful, careful observations of the short stories in ‘Life After God‘. ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’s magical realism throws all that in the air, with the end of the world – fine, I like apocalypse tales as I said – but I struggled with ‘Miss Wyoming’s middle ground: the every day mixed in with the contrived, the titular beauty pageant winner being the sole, completely unscathed, survivor of a plane crash and a strained detective story, culminating in a lackluster, anti-climatic showdown at a gas station. When I first came to it (and probably during that revelatory re-read too), I was frustrated that this very human tale of alienation was ruined by such silliness. It was only later, when I read Coupland’s even later books (All Families are Psychotic, Hey Nostradamus!, etc), that I realised how the choice of that word – alienation – was particularly apt: he’s telling a tale about alienation by alienating us from the story. It’s almost Brechtian – the use of the third person/limited perspective physically removes us from the heart of the narrative and the contrived, unbelievable plot points distract us further still. Both of these things – along with the stilted style I mentioned up top – remind us that we’re in a constructed story, not a simple representation of reality, and prevent us from emotionally engaging too closely with the characters so that we focus more on the underlying messages.

What, then, is the core, underlying message of ‘Miss Wyoming’ that I keep going on about? Well, it is what we’ve heard before: it’s about the hollowness of traditionally-defined success, lost people finding each other and change is hard but it’s worth it – that common, contradictory Coupland blend of ‘modern life is shit’ optimism. Away from Susan’s plane crash survival, we follow John Lodge Johnson, a big shot Hollywood producer, who hits rock bottom and clinically dies, then decides to turn his back on his life and become a hobo. But instead of finding Kerouac’s idealism, a mythical wisdom of the road, he gets beaten up, has a severe food poisoning and comes to the realisation that the vision he’d had at death’s door that set him on his way was … nothing – it wasn’t a magical message from heaven but just his brain feeding back snippets of an old tv show. When I came back to the book in 2002, I was watching those around me – the ex-boyfriend, my other friends – try to reinvent themselves while staying in the same place, surrounded by the same people who held set ideas about them. Struggling myself, I was tempted with the idea of ripping up my roots and starting over – there was little holding me in Leeds then and I felt like I wanted a clean break of the type I didn’t get at the end of university: I’d never have been brave enough to do what John Johnson did anyway but I think seeing his failure was an important counter to the romance of the escaping – I would still be me, fucked up me, wherever I went. (This is what depresses me about the end of ‘Ghost World’ – I want to be optimistic for Edna but I doubt it ends well for her.) So once again, it comes down to finding our tribe – those human connections that feel like “salve on a burn [we] didn’t know [we] had”. Vanessa finds Ryan. Susan finds Eugene & Randy. John finds Susan – and Ryan & Vanessa.

So that was back then, at 22, fifteen years ago. I’m at the age now where Coupland was when he was writing this – and the age of John in the novel. In the first chapter, John says:

“I think about how old I am and I wonder ‘Hey John Johnson, you’ve pretty much felt all the emotions you’re ever likely to feel and from here on it’s reruns‘ and that totally scares me. Do you ever think about that?”

I do, John, I do. But I think we’re both wrong. I think we – me, and the fictional John Johnson – have both enjoyed an extended emotional adolescence. After a childhood illness, John hits the ground running and achieves career success at a young age – but his love of partying prevents real emotional progress before his collapse so afterwards, his walkabout acts as a rumspringa – the first time in his life when he’s really considered what he wants or needs on a deeper level. Similarly, growing up in the public eye of beauty pageants and later, network TV, Susan struggles to escape the public’s perception of her – a beauty queen, a younger sister on an 80s sitcom, a wild child wife of a rock star. It is only when her plane crashes and she has a chance to escape that her life can – and does – move on. I think if John had asked the pre-plane crash Susan that question about emotional reruns, she’d have agreed but instead she subtly demurs – and that’s one of the things that attracts John to her: it seems like she has already moved on to the next level and he wants helping up there himself. This desire to move on is a common theme for Coupland’s early works – it’s what Andy, Dag & Claire are looking for in ‘Generation X’, what Dan is looking for in ‘Microserfs’ before he gets together with Karla, and what nearly all the characters want in ‘Girlfriend in a Coma’. Alongside that apocalypse fiction, I have long been a fan of coming of age fiction and as I’ve grown older myself, I’ve recognised that coming of age doesn’t just happen in your teenage years: one of my favourite things about Curtis Sittenfeld’s ‘American Wife’ is that it is about a woman coming of age/becoming who she is in her 30s and beyond – it gives me hope that I still have room to change and the strength to do it without an ill-advised dash into the wilderness.

“I don’t want to go back down there to my crappy little life.”

“Your life is crappy?” …

“It’s not what I would have wanted, no.”

“What would you have wanted then?”

“Like I keep that information at the top of my ‘To Do’ list, or something?”

“What would be wrong with keeping that at the top of your ‘To Do’ list?”

As with ‘Generation X’, I’m not sure I would recommend ‘Miss Wyoming’, especially not to Coupland newbies. It’s jarring, it’s stilted, it’s clunky – and unless you understand that’s the point of it, it’s not going to go down smoothly. But I’ll return to it again.

Final Thoughts

In ‘Generation X’, Andy describes the Vietnam War as being like a colour in his childhood – he is too young to remember the detail but it was always there, like the colour green, and when it ended, it was as strange as if the colour green went away. I suppose I feel this way about Douglas Coupland’s early novels – they were such a formative part of my late adolescence that they coloured my life and I suspect I will return to them again and again over the years but I don’t think I’m going to push on any further with Coupland’s catalogue at this time. The rest of his books don’t mean as much to me – I have them all on my shelf, but *sssh* I don’t think I’ve even read the last two.

This re-examination – both the re-reading and this reviewing – has been interesting though. If you had asked me a few weeks ago to name the over-riding themes in these early books I would have probably mumbled “uh, people looking for the answers away from the mainstream” and then I’d have made a “knee-jerk irony”-style comment then run away. But looking more closely at the shared elements between these books, I feel they’re a lot more optimistic than I would have given them credit for, and more timeless too. Neither of those is a bad thing.

Leave a Reply